Warlock (The Library of America, 2020)

by Oakley Hall

USA, 1958

"Is not the history of the world no more than a record of violence and death cut in stone?"

(Warlock, 1067)

A McCarthy era novel about frontier justice in the early 1880s American southwest (the town of Warlock seeming to be an only thinly disguised approximation of Tombstone, AZ) that interrogates America's long infatuation with vigilantism and bloodlust, our penchant for building up and tearing down heroes, and the tension between lawlessness and state overreach in the name of putting down "disorder." Sort of a strange batch of concerns for a tome which in other respects can be enjoyed as a juicy, compulsively readable page-turner, but I guess Hall (1920-2008) knew what he was doing when he set out to write about the shit that'd hit the fan once renowned gunslinger Clay Blaisedell was installed as acting Marshal by a Citizens' Committee to bring peace to the growing but government-less town plagued by badmen, road agents and "Cowboys who have an especial craving to ride a horse into a saloon" (569) among other scourges. Sometimes hailed as a proto-Cormac McCarthy era "revisionist western," a comparison that does justice to both authors even if the term "revisionist western" strikes me as inherently dodgy when applied to fiction rather than history, I get what people mean by that even though Warlock's charms seem more rooted in traditional storytelling (plot over language, for example) than the later novelist's. Still, Blaisedell's successes, as measured by the # of dead bodies of men who mostly deserved what they got but accompanied by the loss of life of others who were merely in the wrong place at the wrong time, eventually frustrates much of the fickle townsfolk to the point that even a nominal supporter, the shopkeeper Henry Holmes Goodpasture, is moved to lament in his journal that "The earth is an ugly place, senseless, brutal, cruel, and ruthlessly bent only upon the destruction of men's souls. The God of the Old Testament rules a world not worth His trouble, and He is more violent, more jealous, more terrible with the years. We are only those poor, bare, forked animals Lear saw upon his dismal heath, in pursuit of death, pursued by death" (839). A McCarthyesque sentiment, no? As is this pronouncement from the exasperated, drunken Judge Holloway: "People don't matter a damn. Men are like corn growing. The sun burns them up and the rain washes them out and the winter freezes them, and the cavalry tramps them down, but somehow they keep growing. And none of it matters a damn so long as the whisky holds out" (1011). A fine, fine read.

Oakley Hall and his wife Barbara in 1985

(photographer unknown)

*

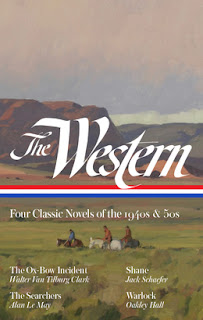

I read Warlock in the LOA anthology The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s and 50s (New York: The Library of America, 2020, 581-1079).

One of Pynchon's rare reviews. (He liked it.) I've been meaning to read it since I came across his review, but haven't.

ResponderBorrarI've read that Pynchon was a fan of Warlock, which surprised me somewhat in that it seems a very old-fashioned novel in relation to Pynchon's own body of work (caveat--I only know Pynchon by reputation). Hall's novel is very well-crafted, though, and a universe unto itself in some ways. Good stuff.

BorrarThe Pynchon review, read long ago when I tracked down every word of Pynchon, made me curious, too, but I guess not enough to actually read the book, so thanks,

ResponderBorrarI'm pretty wary of both contempo (or near contempo in this case) American fiction and historical fiction in general so I was thrilled that this so lived up to the hype. It did temporarily postpone a planned Cormac McCarthy/Faulkner combination read I had in mind, but I'm not complaining at all.

Borrar