Life A User's Manual [La Vie mode d'emploi] (David R. Godine/Verba Mundi, 2009)

by Georges Perec [translated from the French by David Bellos]

France, 1978

"Is he having us on?"

Gabriel Josipovici. "Georges Perec's Homage to Joyce (And Tradition)."

In The Yearbook of English Studies, Vol. 15 (1985), Anglo-French Literary Relations Special, p. 188.

Getting to know Georges Perec, the author of Life A User's Manual and hence the object of an incipient man crush on my part, through the reading of his most celebrated novel, I frequently found myself asking: Georges, where have you been all my life? In between such possibly spurious moments, I really did laugh out loud and shake my head in disbelief throughout this work in appreciation of its extreme inventiveness and sheer narrative exuberance. Oft labeled an "experimental" novel on account of its jigsaw puzzle-like structure and the fact that most book bloggers are too lazy to consider reading it, Life is perhaps better thought of as a sort of distant cousin to the reader-friendly likes of The 1001 Nights, Boccaccio's Decameron, and Ovid's Metamorphoses. An exercise in storytelling for storytelling's sake. A vast storehouse of stories enhanced and enriched by imaginative allusions to other stories and storytellers. While one thread of the ingeniously-constructed plot revolves around millionaire British eccentric Bartlebooth's fifty year project to assemble and then disassemble a series of 500 seascapes-turned jigsaw puzzles in an act of futility that may or may not hold any special meaning for him, another has to do with Bartlebooth's neighbor, associate, and puzzlemaker extraordinaire Gaspard Winckler's plan to exact revenge on the Englishman for some unspecified reasons. As new details about the struggle between these "two senile monomaniacs churning over their feigned histories and their wretched traps and and snares" (250) begin to emerge from the void (seemingly bringing order to the descriptive chaos), the narrative itself takes on the shape of yet another 750-piece puzzle as it mimics the form of French artist Valène's scarcely less ambitious plan to paint the Parisian apartment building where all the principal characters live as if it were a giant doll's house with the facade removed: room by room, object by object in painstaking detail, as imagined at a moment in time later to be revealed as the precise moment of Bartlebooth's death. The result is a mystery--or if you prefer, a puzzle--fragmentarily assembled in such a way that all of the characters' neighbors and many former inhabitants of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier become an integral part of the extended cast with a corresponding domino effect on the storylines that's just incredible to behold. And the result is a mystery--or if you prefer, a puzzle--told in such a way that while the painter's perspective often seems to double as the narrator's, woe to the careless reader who succumbs to the page-turning charms of the story and doesn't take note of all the funhouse and trompe l'oeil effects Perec's set up as snares along the way. Just a super fun read that makes me want to smack my lips and say...C'est magnifique! (http://www.godine.com/)

Georges Perec

A Technical Note

I had some story-related thoughts I wanted to add here regarding Perec's use of altered quotations as a form of creative "plagiarism" and the significance of Gaspard Winckler's revenge and such, but I think I'll save those for the comments box if anyone in our little readalong group would like to discuss them. For now, though, I'd like to touch on two technical aspects of Life A User's Manual that continue to blow my mind. First, the constraints. Many of you are probably aware that Perec imposed a series of constraints upon himself during the writing of this novel. Although it's easy enough to find information on this in English online, I'd like to direct your attention to this French site here for the best one-stop visual grid I've seen of the various tables Perec used to pair specific author references and other allusions throughout the novel (my favorite categories: missing and false, two "wild cards" if you will). To see how the table's used, click on any of the contraintes, say "citation 1" or "citation 2" or "couple 1" or "couple 2," to view the authors that needed to be cited or the "couples" (Laurel and Hardy, crime and punishment, etc.) required to be mentioned chapter by chapter throughout the entire novel. Just nuts! Second, I'd like to return to the Knight's Tour mentioned earlier in the month when I was first getting into the novel. You don't have to know anything about this technique to appreciate Perec's storytelling for its entertainment value, but once again, man, is that crazy! However, the extremely-observant Isabella of Magnificent Octopus recently pointed out that Perec seems to have "cheated" on one of his moves. Her question: What happens between chapters 65 and 66? Although I tried to figure this out using Perec's hint that a "little girl" was to blame for this problem, I couldn't figure out what he was talking about since the page numbers cited didn't have anything to do with my edition of the novel. Doing a little detective work last night on JSTOR, I came across the answer and learned why it was such a mystery: it has to do with French wordplay that got lost in translation! Bear with me for this fairly long but quite elegant explanation courtesy of Paul A. Harris:

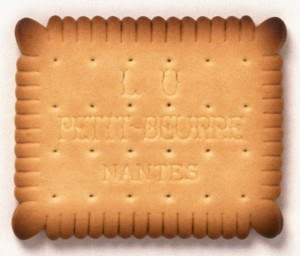

A more consciously contrived perturbation in the formal structure of the book is that while the building has 100 rooms, Life A User's Manual has only 99 chapters. The room described in the text, found at the extreme bottom left corner of the 10 x 10 board, would be the 66th chapter. At the end of chapter 65, a list of knickknacks concludes with a square biscuit box on which a girl is seen "munching the corner of her petit-beurre" (318). The girl has nibbled off the corner of the board map for the book, eating the chapter in the process. The connection between the biscuit box and 10 x 10 square of rooms is conveyed through an operation of verbal transformation favored by Perec, that of homophones (see Magné 1986, 61-62). In the original, the square tin box is "fer-blanc, carrée" (Perec 1978, 394); the result of the girl nibbling is "faire un blanc dans le carré" (Magné 1990, 14). And the whole conception of this clinamen is contained in a pun in French, for one "pièce" (room and/or puzzle piece) in the book can't find its place--a foreshadowing of the piece that Bartlebooth dies holding, the last piece in a puzzle whose shape is an X, while the blank space forms a W.*

So what the heck is a clinamen? I'm glad you asked because this further exposes the fine line between Perec's sense of humor, genius, and "madness" if you ask me! According to my trusty handbook, "For Oulipians, the clinamen is a deviation from the strict consequences of a restriction. It is often justified on aesthetic grounds: resorting to it improves the results." So far, so good--but check this out. "But there is a binding condition for its use: the exceptional freedom afforded by a clinamen can only be taken on the condition that following the initial rule is still possible. In other words, the clinamen can only be used if isn't needed [underscore added]."** On that note, I'm off to bed but will be eager to discuss Life A User's Manual with any and all concerned in the morning (send me your links!).

*Paul A. Harris. "The Invention of Forms: Perec's Life A User's Manual and a Virtual Sense of the Real." In SubStance 23(2), Issue 74, pp. 63-64.

**Harry Mathews and Alastair Brotchie, eds. Oulipo Compendium. London: Atlas Press, 2005, p. 123.

un petit-beurre, yummy

(naturally, "lu" also means "read" [past participle] in French, ha ha!)

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Bellezza (Dolce Bellezza), 1

Bellezza (Dolce Bellezza), 2

Claire (kiss a cloud), 1

Claire (kiss a cloud), 2

E.L. Fay (This Book and I Could Be Friends), 1

Bellezza (Dolce Bellezza), 1

Bellezza (Dolce Bellezza), 2

Claire (kiss a cloud), 1

Claire (kiss a cloud), 2

E.L. Fay (This Book and I Could Be Friends), 1

Emily (Evening All Afternoon), 1

Frances (Nonsuch Book), 1

Frances (Nonsuch Book), 2

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 1

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 2

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 3

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 4

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 5

Julia (A Number of Things), 1

Julia (A Number of Things), 2

Julia (A Number of Things), 3

Julia (A Number of Things), 4

Sarah (what we have here is a failure to communicate), 1

Frances (Nonsuch Book), 1

Frances (Nonsuch Book), 2

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 1

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 2

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 3

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 4

Isabella (Magnificent Octopus), 5

Julia (A Number of Things), 1

Julia (A Number of Things), 2

Julia (A Number of Things), 3

Julia (A Number of Things), 4

Sarah (what we have here is a failure to communicate), 1