by Thomas Bernhard [translated from the German by David McLintock]

Austria, 1984

Vienna is a terrible machine for the destruction of genius, I thought, sitting in the wing chair, an appalling recycling plant for the demolition of talent. All these people whom I was now observing through their sickening cigarette smoke came to Vienna thirty or thirty-five years ago, hoping to go far, only to have whatever genius or talent they possessed annihilated and killed off by the city, which kills off all the hundreds and thousands of geniuses or talents that are born in Austria every year.

(Woodcutters, 56)

Even though it sometimes seems as if apocalyptic kvetcher Thomas Bernhard might be something of a one-trick pony for his unhinged but been there/done that monologic book-length rants, what a trick--and what a pony! Woodcutters, the much ballyhooed centerpiece of the writer's so-called arts trilogy, finds the post-Karl Kraus Austrian king of mischief administering a world class beating to the Viennese theater world and its champions and, by extension, lamenting the myriad ways even non-actors and non-artists preference dishonesty over honesty and pretense to reality in their personal dealings. Who: an unnamed narrator, observing it all from the vantage point of a "hideous" Viennese apartment's wing chair while partaking of copious amounts of expensive champagne. What: a dinner party from hell, an artistic dinner designed to impress the hosts' status-conscious and/or otherwise shallow friends, with a late-arriving and pretentious actor from the Burgtheater starring as the guest of honor. When: sometime in the 1980s, around midnight on the evening following the funeral of a friend of many of the dinner guests. Where: at the Auersbergers' home in the Gentzgasse in Vienna, a place that the narrator hasn't visited for years and wishes he hadn't visited now. Although a perfectly chosen Voltaire epigraph ("Being unable to make people more reasonable, I preferred to be happy away from them") starts the anti-social ball rolling so to speak, as usual it's Bernhard's agreeably disagreeable narrator who dishes out most of the comedic fun and/or punishment ("To serve potato soup at a quarter to one in the morning and announce that a boiled pike is to follow is a perversion of which only the Auersbergers are capable, I said to myself" [100]). On a related note, here are three amusingly class-conscious examples of Bernhardian wit that show how the narrator targets the bourgeois, the petit bourgeois, and the proletariat in his indictment of virtually all of Austrian society. On the talented musician turned social climber and drunk Auersberger: "His attempts at upward mobility into the aristocracy came to grief even more pitifully and calamitously than [his wife's]. It was, as I know, his life's ambition to be an aristocrat, nothing less: the sad truth is that he would rather have been a witless aristocrat than a respectable composer" (83). On the gifted writer turned conformist has been Jeannie Billroth: "I found myself sitting opposite the Virginia Woolf of Vienna, this creator of tasteless poetry and prose who has never done anything throughout her life, it seems to me, but wallow in her petit bourgeois kitsch. And someone like this dares to say that she has surpassed Virginia Woolf, whom I consider the greatest of all woman writers and have admired for as long as I have been competent to form a literary judgment--somebody like this has the temerity to assert that in her own novels she has surpassed The Waves, Orlando and To the Lighthouse" (100). On the wannabe aristocrats who have to sell off land in the country to maintain their sham artistic lifestyles in the city: "Where there was once a copse or a thicket, where a garden once blossomed in spring and its glorious colors faded in the fall, there is now a rank growth of the concrete tumors beloved of our modern age, which no longer has any thought for landscape or nature, but is consumed by politically motivated greed and by the base proletarian mania for concrete, I thought, sitting in the wing chair" (86). "The base proletarian mania for concrete" may be a hard line to top, but what does the narrator have to say about the theater world itself? Hmm, should I opt for the crowd-pleasing option on pages 16-17, the one that speaks about the guest of honor as "the personification of the anti-artist...the archetypal mindless ham, who's always been popular at the Burgtheater and in Austria generally, utterly devoid of imagination and hence of wit, one of those unspeakable emotionalists who tread the boards of the Burgtheater every evening in droves, wringing their hands in their unnatural provincial fashion, falling upon whatever work is being performed, and clubbing it to death with the sheer brute force of their histrionics"? Or should I close with that nice, unsettling funeral option from page 57 instead? Yes, I think that's just the ticket for this crowd--hope I guessed right:

What a depressing effect the funeral at Kilb had on me, for this reason more than any other! I thought, watching these people from a wing chair. What depressed me was not so much the fact that Joana was being buried as that the only people who followed her coffin were artistic corpses, failures, Viennese failures, the living dead of the artistic world--writers, painters, dancers and hangers-on, artistic cadavers not yet quite dead, who looked utterly grotesque in the pelting rain. The sight was not so much sad as unappetizing, I thought. All through the ceremony I was obsessed by the spectacle of these repellent artistic nonentities trudging behind the coffin through the cemetery mud in their distasteful attitudes of mourning, I told myself as I sat in the wing chair. It was not so much the funeral that aroused my indignation as the demeanor of the mourners who had turned up from Vienna in their flashy cars. I became so agitated that I had to take several heart tablets, yet my agitation was brought on not by the dead Joana, but by the behavior of these arty people, these artistic shams, I thought, and it occurred to me that my own behavior at Kilb had probably been equally distasteful.

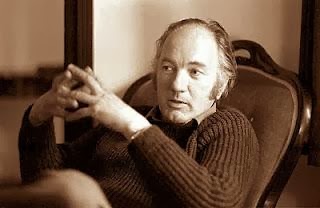

Thomas Bernhard (1931-1989)