lunes, 1 de mayo de 2023

sábado, 29 de abril de 2023

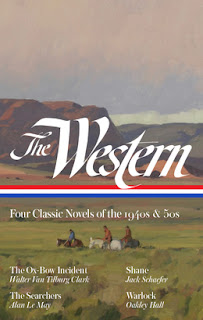

Warlock

Warlock (The Library of America, 2020)

by Oakley Hall

USA, 1958

"Is not the history of the world no more than a record of violence and death cut in stone?"

(Warlock, 1067)

A McCarthy era novel about frontier justice in the early 1880s American southwest (the town of Warlock seeming to be an only thinly disguised approximation of Tombstone, AZ) that interrogates America's long infatuation with vigilantism and bloodlust, our penchant for building up and tearing down heroes, and the tension between lawlessness and state overreach in the name of putting down "disorder." Sort of a strange batch of concerns for a tome which in other respects can be enjoyed as a juicy, compulsively readable page-turner, but I guess Hall (1920-2008) knew what he was doing when he set out to write about the shit that'd hit the fan once renowned gunslinger Clay Blaisedell was installed as acting Marshal by a Citizens' Committee to bring peace to the growing but government-less town plagued by badmen, road agents and "Cowboys who have an especial craving to ride a horse into a saloon" (569) among other scourges. Sometimes hailed as a proto-Cormac McCarthy era "revisionist western," a comparison that does justice to both authors even if the term "revisionist western" strikes me as inherently dodgy when applied to fiction rather than history, I get what people mean by that even though Warlock's charms seem more rooted in traditional storytelling (plot over language, for example) than the later novelist's. Still, Blaisedell's successes, as measured by the # of dead bodies of men who mostly deserved what they got but accompanied by the loss of life of others who were merely in the wrong place at the wrong time, eventually frustrates much of the fickle townsfolk to the point that even a nominal supporter, the shopkeeper Henry Holmes Goodpasture, is moved to lament in his journal that "The earth is an ugly place, senseless, brutal, cruel, and ruthlessly bent only upon the destruction of men's souls. The God of the Old Testament rules a world not worth His trouble, and He is more violent, more jealous, more terrible with the years. We are only those poor, bare, forked animals Lear saw upon his dismal heath, in pursuit of death, pursued by death" (839). A McCarthyesque sentiment, no? As is this pronouncement from the exasperated, drunken Judge Holloway: "People don't matter a damn. Men are like corn growing. The sun burns them up and the rain washes them out and the winter freezes them, and the cavalry tramps them down, but somehow they keep growing. And none of it matters a damn so long as the whisky holds out" (1011). A fine, fine read.

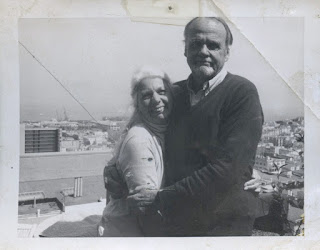

Oakley Hall and his wife Barbara in 1985

(photographer unknown)

*

I read Warlock in the LOA anthology The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s and 50s (New York: The Library of America, 2020, 581-1079).

domingo, 9 de abril de 2023

The Golem

The Golem [Der Golem] (Dedalus, 2020)

by Gustav Meyrink [translated from the German by Mike Mitchell]

Austria-Hungary, 1915

Borges called The Golem "admirablemente visual" ["admirably visual"] in style and "un libro único" ["a unique book"]. Karl Kraus famously lampooned Meyrink's body of work as combining "Buddhism with a dislike for the infantry." Closer to home, Amateur Reader (Tom) has said that Meyrink was "semi-obscure, semi-difficult, obviously not a first-rate writer but easily worth a look or two or three." What could I possibly add to the discussion after those three titans of book talk have weighed in? I'll give it a try by noting that The Golem is nominally the story of one Herr Athanasius Parnath, an amnesiac and/or just plain mad gemcutter living in and working out of Prague's old Jewish ghetto, and a man who may be the doppelgänger of both the frame story narrator of the novel as a whole and the murderous Golem himself (note: the antics move to the beat of their own dream logic here). While at times confusing and, what's worse, a horrorless, occultist horror novel in a way, the dated weirdness of the work makes it easy enough to embrace even today. I loved, for example, the expressionist descriptions of the people and the places in the ghetto as well as its sights and sounds. Parnath at one point claims to finally understand "the innermost nature of the mysterious creatures that live around me," suggesting that they "drift through life with no will of their own, animated by an invisible, magnetic current, just like the bridal bouquet floating past in the filthy water of the gutter." For a follow-up, he adds that "I felt as if the houses were staring down at me with malicious expressions full of nameless spite: the doors were black, gaping mouths in which the tongues had rotted away, throats which might at any moment give out a piercing cry, so piercing and full of hate that it would strike fear to the very roots of our soul" (45-46). Of course, the image of "a tinkling sound from the piano, as if a rat were running along the keys" (66) was also a nice audiovisual touch. In addition to the pre-The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari-like visual shenanigans, I was also tickled by Meyrink's pulp sensibilities both w/r/t the references to ghetto slang ("In their jargon [a 'Freemason'] was a name for a man who had sexual relations with schoolgirls but whose connections with the police render him immune to the legal consequences" [47]) and the random, proto-Arltian descriptions ("He was stretched on the rack of the deathly hush in the tavern") and dialogue ("You can recognise scum by their sentimentality") (76 & 205) as well as the Baudelaire- and Lautréamont-like encomium to a murderer and suicide which climaxes with the declaration that "the poisonous autumn crocus is a thousand times more beautiful and noble than the useful chive" (238). Hugo Steiner-Prag, an artist who knew the real-life Jewish quarter in Prague before it was demolished and did the illustrations for the first editions of Meyrink's Golem, was to have written a non-opium dream chronicle of the Ghetto but it was left unfinished at his death. What a bland and colorless pity.

Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932)

lunes, 3 de abril de 2023

Mapocho

Mapocho (Eterna Cadencia Editora, 2019)

por Nona Fernández Silanes

Chile, 2002

La Rucia y el Indio son hermanos que, después de haber vivido en el extranjero por muchos años, regresan a Chile después de la muerte de la madre. Al llegar a Santiago, la Rucia deambula por la ciudad en busca de su hermano --el plan: reunirse para tirar las cenizas de la madre en el río Mapocho, "su río" y "su ciudad" según el Indio (16) pero un "conjunto de mojones y basura" según otro tipo (41)-- y se queda en la casa de su infancia ahora casi en ruinas en un barrio ahora casi irreconocible también. Fausto, un historiador que entre sorbos de whisky afirma que "los muertos viven" y que "él puede verlos" y que uno "puede tocarlos, hablarles y hasta consolarlos si se le acercan a llorar" (107), se encuentra con la Rucia al entierro de sus propios hijos al cementerio, donde las vidas de las dos se cruzan y un panorama de la historia chilena empieza a aclararse en un mundo fantasmal parecido a lo de Pedro Páramo de Rulfo. Qué estupenda novela esta. Supondría, por ejemplo, que es un reto de un alto grado de dificultad escribir algo realista en el que personajes muertos hablan de "morir y no saberlo" (130) o se quejan a la Virgen que "los vivos y los muertos se nos están mezclando y tú sabes que eso no es bueno. Caminan por las mismas calles, rezan en las mismas iglesias, algunos hasta conversan entre ellos sin respetar los límites divinos. Ya nadie entiende nada aquí abajo, es una verdadera casa de putas" (200). Yo también me imagino que no pudo haber sido fácil lidiar con las falsedades y las mentiras particular a la historia oficial de Chile en una breve obra de ficción, pero Fernández (Santiago de Chile, 1971), que en el epílogo de 2018 describe la génesis de Mapocho como una foto de tres cadáveres encontrados "tirados en la orilla del río" en septiembre de 1973 (231), tiene éxito más allá de todas las expectativas con la ferocidad y la rabia de su prosa --"La mentira tiene alas y vuela como un buitre, ronda sobre la carroña y se alimenta de los que no saben, los que no ven o no quieren ver" (171); "La mentira respira, huele, chilla, vive como un ratón del Mapocho alimentándose de la mierda, contaminando, expandiendo la enfermedad, pudriéndolo todo, creando más mentira, mintiendo sobre mintiendo, enredando, confundiendo, cahuineando" (172). Inquietante al enésimo grado pero un golazo estilísticamente y temáticamente hablando.

Nona Fernández Silanes

sábado, 1 de abril de 2023

domingo, 26 de marzo de 2023

Vita Nuova

Vita Nuova (Penguin Classics, 2022)

by Dante Alighieri [translated from the Italian by Virginia Jewiss in a dual language edition with parallel text]

Florence, c. 1292-1295

Enigmatic but somehow super interesting libello of poems and prose commentary ("somehow" because the prosimetrum format invites readers--at least readers in translation--to focus on the internal architecture of the work, its narrative arc, the would be autobiography contained within it, its author's poetic coming of age story, essentially everything but Dante's poetry in deference to his prose). I'll certainly have my work cut out for me if I ever read it again! For now, though, I think it'll be enough to mention a handful of things that stood out to me. As Virginia Jewiss conveniently points out in her introduction, "The essential, unsettling claim of the Vita Nuova is this: Beatrice, a real woman from Florence, is also a miracle, a disruptive, divine force who intervenes in [Dante's] life, causing him to think, to write, and to love in new ways. And, miracle that she is, she continues to do so after she dies, disrupting even the finality of death" (viii). The potential sacrilege of this conceit aside, the way Dante chooses to approach it in the context of traditional love poetry is jarring in the extreme. In Chapter 3, for example, he shares a vision in which a "lordly figure" persuades the dream version of Beatrice, described as "naked save for a loosely wrapped crimson cloth," to eat Dante's "burning" heart before ascending to heaven with her. Even accepting the lordly figure as the personification of Love and allowing leeway for the poet to operate freely in the symbolic realm, the impact of the imagery still seems almost Book of Revelation visionary to me--not at all what was expected. As odd as the combination of religious and love poetry here can be at times, though, the Vita Nuova also provides ample evidence that Dante knew how to up the ante. In Chapter 7, he explains that he wrote a sonnet in which his intent was to "call on Love's faithful with the words of the prophet Jeremiah, 'O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite e videte si est dolor sicut dolor meus,' and to beg them to listen to me." The allusion, which Jewiss attributes to Lamentations 1:12 and translates as "All you who pass along the way, stay here a while, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow" (21), is a fine example of Dante's intertextual dexterity insofar as the translation of the verse into his sonnet ("You who journey on the path of Love,/stay here a while and see/if there be any grief as great as mine" ["O voi che per la via d'Amor passate,/attendete e guardate/s'egli è dolore alcun, quanto 'l mio, grave"]) foreshadows the lovesick poet's illness-inspired dream in Chapter 23 where presentiments of Beatrice's death find "strange and horrible faces" telling Dante that "you are dead" while "birds in flight fell dead from the sky, and the earth quaked" as an apocalyptic preliminary to the canzone that follows. When Beatrice later does die within the timeline of the work as recounted in Chapter 28, Dante claims that a Lamentations 1:1 allusion he had just written into his canzone ("Quomodo sedet sola civitas plena populo! facti est quasi vidua domina gentium" [Jewiss: "How lonely sits the city that was full of people! How like a widow has she become!"]) was interrupted by the announcement of her death. He then expresses his grief in first prose and then poetry equally powerfully: "Once she had departed from this world, the entire city was like a widow, stripped of all her dignity" ["Poi che fue partita da questo secolo, rimase tutta la sopradetta cittade quasi vedova dispogliata da ogni dignitade"] (Chapter 30); "These eyes, which weep in pity for my heart/have shed so many mournful, plaintive tears/they ache with sorrow but can cry no more" ["Li occhi dolenti per pietà del core/hanno di lagrimar sofferta pena,/sí che per vinti son rimasi omai"] (Chapter 31). The poet's emotions, almost palpable to a reader even several hundred years after they were set down in writing, require no gloss but form a strange kind of coda to the famous earlier Chapter 25 in which Dante verses on the differences between the Latin poets and the vernacular poets and how the recent rise of vernacular poetry in Provençal and Italian, "the languages of oc and of sì," was due in Italy at least to the fact that "the first to begin writing poetry in the vernacular was moved by the desire to make his words understood by a woman who found Latin verses hard to understand." Wild.

La visione: Dante e Beatrice

(Ary Scheffer, 1845)

domingo, 19 de marzo de 2023

Los sorrentinos

Los sorrentinos (Sigilo, 2022)

por Virginia Higa

Argentina, 2018

"El Chiche Vespolini era el menor de cinco hermanos, dos varones y dos mujeres. Su verdadero nombre era Argentino, pero le decían así porque de chico era tan lindo y simpático que se había convertido en 'el chiche de sus hermanas'. Los Vespolini se habían instalado en Mar del Plata a principios de 1900 y siempre habían tenido hoteles y restaurantes. De su familia el Chiche había heredado la Trattoria Napolitana: el primer restaurante en el mundo en servir sorrentinos".

Así empieza Los sorrentinos, de Virginia Higa (Bahía Blanca, 1983), una novela divertida basada en un retrato de familia convertido en ficción al estilo de Natalia Ginzburg o algo así (tengo entendido que el Chiche era el tío bisabuelo de nuestra autora). Si no está claro dónde se encuentra la línea entre la realidad y la ficción dentro de la novela, me da igual porque me gustó la filosofía culinaria del Chiche (dos máximas suyas: "Cada pasta tiene su personalidad" y "La cocina del sur de Italia es la unión perfecta entre lo alto y lo popular" [12 y 52]) tanto como el excéntrico elenco de personajes (por ejemplo, el primo Ernesto, de ragazzo casi adoptado por un tal Máximo Gorki durante una visita a Italia, solía lamentar "Yo podría haber sido un bolchevique" durante las sobremesas familiares [35]) además del sentido de humor de varias personas vinculadas con o la familia o la trattoria ("Las cocineras y las camareras decían que Valdemar era buen mozo, 'un churrasco'. Carmela no estaba de acuerdo: 'Para churrasco le sobra un poco de grasa'" [124-125]). Por su parte, Higa demuestra un toque ligero alternando entre lo anecdótico y el lado nostálgico de las cosas. También me interesó el léxico familiar de los Vespolini ("Entre ellos hablaban en lengua napolitana" [32]) y la manera en que el asunto de la "italianidad" de todos estos marplatenses podría expresarse en insultos ("¡Catrosha, no digas papocchias!" [74]) o preguntas sencillas ("¿Te acordás de cuando éramos imperio? ¡Qué grande era el emperador Augusto!" [19]) con igual facilidad. Genial.

Virginia Higa

(foto: Bernardino Avila)

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)

.jpg)