Yo el Supremo (

Cátedra, 2005)

by Augusto Roa Bastos

Argentina, 1974

If you'll pardon the effrontery of me shamelessly quoting from my own intro post on

Yo el Supremo, I'd like to reformulate a question that I'd thought at the time might be best for us to save/savor/save for later: what's the point of spending several hundred pages with

Yo el Supremo just to witness the title character eventually entombing himself in a mausoleum of words? To start with, the novelty or the entertainment value of Roa Bastos' storytelling should be clear enough from the fact that I haven't even had time to talk about things like either a) the blanket--"más blanda que la seda, el terciopelo, el tafetán o la holanda era" ["softer than silk, velvet, taffeta, or fine Dutch linen it was"]--that Don Mateo Fleitas, an early Supremo/Supreme scribe discusses with Policarpo Patiño (?-1840), the current Supremo/Supreme scribe according to the main timeline in the novel, and which he says he fashioned out of the skin of innumerable long-eared bats: "Va a ser una manta única en el mundo. Suave, ya la ha tocado usté mismo. La más liviana. Si la tiro al aire en este momento, usté y yo podemos envejecer esperando que vuelva a caer. La más abrigada" ["There will never be a blanket like it in this world. Soft, you've already touched it yourself. Couldn't be lighter. If I toss it in the air at this moment, you and I will become old and gray as we wait for it to fall back down. Couldn't be better insulation"] (121 in the original, 26-27 in Helen Lane's translation) or b) the Supreme's occasional anthropological disquisitions on Guaraní culture like the one where he claims that in Paraguay, "donde el demonio es hembra para los nativos, algunos tribus rinden culto a este súcubo" ["where the devil is a woman for the natives, certain tribes worship this succubus"] in the form of "la vulva-con-dientes" ["the vulva-with-teeth"]: "¿No caen esos dientes, Excelencia, a la vejez de la hembra? No, mi estimado don Juan. Se vuelven cada vez más filosos y duros. ¿Teme algo? ¿Le ha sucedido algo desagradable?" ["Don't those teeth fall out, Excellency, when the woman grows old? No, my dear Don Juan. They become harder, even sharper. Is there something you're afraid of? Has something unpleasant happened to you?"] (258 in the original, 138 in the translation). A less racy comment by the perpetual dictator suggesting that the natives' conception of male/female types as essentially hermaphroditic is responsible for having "anularon la distinción de los sexos, tan cara e indispensable al pensamiento occidental, que únicamente sabe manejarse por pares" [canceled out "the difference between the sexes, so dear and so indispensable to Western thought, which can operate only by pairs"] induces the Compiler to namedrop Jorge Luis Borges'

Historia de la eternidad [

History of Eternity] in a footnote, which in turn leads to a mention of Leopoldo Lugones'

El Imperio Jesuítico [

The Jesuit Empire] and etc. and etc. and on to infinity

(249-250 in the original, 132 in the translation).

Roa Bastos, who claimed that Borges and Juan Rulfo were two of his favorite writers in an interview I came across recently but can't find at the moment, finds another way to riff on the Borgesian dimensions of time here: the Compiler

claims that

el Supremo solved a riddle posed by Nietzsche and written about by Borges in yet another work of his!

Structurally and thematically,

Yo el Supremo rewards time spent with it for the way it invites the reader's active participation, debate and even dissent. On the first point, note that even though the subjectivity of the protean, fictional force of nature who is the title character often seems to dominate the proceedings via the character's spluttering insults and his claustrophobic interior monologues about his political legacy and the power of words ("Se escribe cuando ya no se puede obrar" ["One writes when one can no longer act"], he says at one point, inadvertently insulting bloggers everywhere [143 in the original, 45 in the translation]), in reality--if you'll pardon the expression--this domineering first-person POV is constantly challenged by a metaphorical verbal dictatorship of the proletariat represented by the compiler character as well as the various historians and literary figures whose own voices of anti-authoritarian authority hold a mirror up to el Supremo's distorted version of "reality" as if in protest.

Yo el Supremo vs.

Yo el Supremo, dig? To give you an idea of just how intricate and juicy this can be from an unreliable narrator standpoint, I need only point to the sequence where the Supreme mentions sending his envoy Amadís Cantero to a meeting with a Brazilian diplomat named Correia da Cámara over a proposed Brazilian/Paraguayan alliance against Argentina. Keep in mind that at least the Supreme and Correia da Cámara (1783-1848) are historical figures. The Supreme: "Correia da Cámara lo denigrará más tarde en sus informes y memoriales. Será la única vez que diga la verdad" ["Correia da Cámara will later denigrate [Cantero] in his reports and memoranda. It will be the one and only time he tells the truth"] (509 in the original, 347 in the translation). A fragment of a report allegedly lifted from Correa da Cámara's

Anais follows in the form of a footnote, but it's not at all clear whether the change in spelling from

Correia to

Correa is a result of the hispanicization of the name, a switch from archaic spelling to modern spelling, or a hint that this author's

Anais is an imaginary set of "annals" written by a pseudo-Correia. Whatever the case may be, Amadís Cantero, probably at the expense of his über chivalric first name, is indeed denigrated as a "lector de novelas de caballería" ["reader of novels of chivalry"], a "escritor él mismo de bodrios insoportables" ["writer himself of unbearable tripe"], and "el más vil sabandija que he conocido en todos los años de mi vida. Su fuerte es la historia, pero muchas veces hace actuar a Zoroastro en China, a Tamerlán en Suecia, a Hermes Trimegisto en Francia" ["the vilest vermin I have ever known in all the years of my life. His forte is history, but many times he has Zoroaster acting in China, Tamerlane in Sweden, Hermes Trimegistus in France"]. The metafictional insults get more incestuous as the commentary continues. Correa da Cámara: "Noche a noche, me ha estado leyendo algo vagamente parecido a una biografía novelada del Supremo del Paraguay. Abyecto epinicio en el que pone al atrabiliaro Dictador por los cuernos de la luna... ¡Es el tormento, la humillación más atroz, que se me han infligido jamás" ["Night after night he has been reading me something vaguely resembling a novelized biography of El Supremo of Paraguay. An abject dithryamb in which he sets the misanthropic Dictator on the horns of the moon... It is torture, the worst humiliation to which I have ever been subjected!"] (

Ibid., ellipses added). The icing on the storytelling cake? A page or two later, Correa da Cámara mentions a senhor Roa in the course of a diatribe against the Paraguayans' diplomatic tactics. At this point, the unnamed compiler steps in with a footnote of his own regarding the identification of this 19th century "senhor Roa": "El Compilador desea aclarar que el lapsus y la mención no le corresponden; el informe confidencial de Correa menciona textualmente este apellido, según puede consultarse en el tomo IV de Anais, pág. 60 (

N. del C.)" ["The compiler wishes to point out that this lapsus and mention are not attributable to him: Correa's confidential report mentions this name textually, as can be verified in Anais, Volume IV, p. 60.

(Compiler's Note.)"] (511 in the original, 348 in the translation).

Given the multiplicity of perspectives on display in

Yo el Supremo, it shouldn't be surprising to hear that the end of the novel is equally open-ended in terms of the closure--or the lack thereof--that readers can expect to encounter within its final pages. With this in mind, let's take a look how Roa Bastos deals with the legacy of his protagonist. There are, first of all, a succession of endings to the novel rather than just one.

* In the first, a particularly gruesome one, the deceased tyrant holds forth on the various types of "cadaverófilas" ["cadaverophile"] insects which will feast on his rotting corpse (592 in the original, 421 in the translation). The manuscript trails off, and we are told that the following ten folios are unable to be read. Milagros Ezquerro, in a footnote to this passage in the Cátedra edition of the novel, points out that "con esta descripción de las fases de la putrefacción del cadáver se extingue el discurso de El Supremo. Otra voz narradora cierra el espacio textual dirigiéndose a El Supremo y pronunciando su condenación eterna" ["with this description of the stages of putrefaction of the cadaver, El Supremo's discourse is extinguished. Another narrative voice seals the narrative space by addressing El Supremo and pronouncing his eternal condemnation"] (493). The second ending, as we have already noted, is a three page denunciation of the Supreme by an unknown writer who starts by telling the Supreme that "te alucinaste y alucinaste a los demás fabulando que tu poder era absoluto. ¡Perdiste tu aceite, viejo ex teólogo metido a repúblico!" ["you fooled yourself and fooled others by pretending that your power was absolute. You lost your oil, you old ex theologian passing yourself off as a statesman"]. Later, the

Supreme-like chastising

continues with my favorite impertinences being the ones where he/she tells the deceased, "No, pequeña momia; la verdadera Revolución no devora a sus hijos" ["No, little mummy; true Revolution does not devour its children"] (594-595 in the original, 423 in the translation) and, working in a bald joke, "las larvas seguirán pastando en tus despojos tranquilmente. Con sus largos pelos tejerán una peluca a tu calvicie, de modo que tu mondo cráneo no sufra mucho frío" ["the larvae will go on peacefully feeding on your remains. They will weave a wig from its long hairs to cover your baldness, so that your bare skull will not suffer too much from the cold" (596 in the original, 424 in the translation). One subtlety that's unfortunately lost in the English translation of the passage is that the Supreme is addressed throughout with the informal rather than the formal form of the Spanish term for "you" as an additional measure of disrespect. For those keeping score, the beginning of this folio is burned and the ending is illegible and otherwise unable to be found.

Before moving on to the third and the fourth endings to the novel, I think it might be useful for anybody who's only experienced the novel secondhand to know that one of the recurring motifs in

Yo el Supremo is the allegation that either the dictator's skull or a skull believed to belong to the dictator was dug up and decapitated after his death as an act of desecration by his enemies. In one variant of the story, in fact, the skull is said to be stored in a noodle box by a virulent non-fan of the Supreme. Although the Supreme himself makes reference to the story in

this post about his post-mortem friendship with the Argentinean general Belgrano, I decided not to write about the continuation of the scene until now. The Supreme is already dead, of course (403-404 in the original, 256 in the translation):

En cuanto a mí veo ya el pasado confundido con el futuro. La falsa mitad de mi cráneo guardado por mis enemigos durante veinte años en una caja de fideos, entre los desechos de un desván.

Cómo se verá en el Apéndice, también esta predicción de El Supremo se cumplió en todo sus alcances. (N. del Compilador.)

Los restos del cráneo, id est, no serán míos. Más, qué cráneo despedazado a martillazos por los enemigos de la patria; qué partícula de ppensamiento; qué resto de gente viva o muerta quedará en el país, que no lleve en adelante mi marca. La marca al rojo de YO-ÉL. Enteros. Inextinguibles. Postergados en la nada diferida de la raza a quien el destino ha brindado el sufrimiento como diversión, la vida no-vivida como vida, la irrealidad como realidad. Nuestra marca quedará en ella.

As for me, I see the past now confused with the future. The false half of my skull kept by my enemies for thirty years in a box of noodles, amid the junk piled in an attic.

As will be seen in the Appendix, this prediction of El Supremo's was also fulfilled down to the last detail. (Compiler's Note.)

The remains of the cranium, id est, will not be mine. But then, what skull hammered to pieces by the enemies of the fatherland; what particle of thought, what people, living or dead, will there be left in the country who do not henceforward bear my mark? The red-hot brand of I-HE. Entire. Inextinguishable. Left behind in the protracted nothingness of the race to whom destiny has offered suffering as a diversion, non-lived life as life, unreality as reality. Our mark will remain on it.

Still with me? The Appendix referred to above constitutes the third of four endings in Roa Bastos' novel and is the main one encouraging debate concerning the Supreme's legacy (an earlier fragment, in which schoolchildren answer the question of "cómo ven ellos la imagen sacrosanta de nuestro Supremo Gobierno Nacional" ["how they see the sacrosanct image of our Supreme National Government"] also addresses the question in an often humorous fashion) (570 in the original, 403 in the translation). In the Appendix, though, a number of historians and other interested parties weigh in on the specific topics of 1) Los restos de El Supremo [The Remains of EL SUPREMO] and 2) Migración de los restos de El Supremo [Migration of the Remains of EL SUPREMO]. The introduction by an unknown person (the compiler? Roa Bastos? Roa Bastos as the compiler?) states that "el 31 de enero de 1961, una circular oficial convocó a los historiadores nacionales a un cónclave con el fin de 'iniciar las gestiones tendientes a recuperar los restos mortales del Supremo Dictador y restituir al patrimonio nacional esas sagradas reliquias'" ["on January 31, 1961, an official circular invited historians of the nation to a conclave, in order to 'initiate steps leading to the recovery of the mortal remains of the Supreme Dictator and the restoration of these sacred relics to the natural patrimony'"] (597 in the original, 425 in the translation). In a mocking tone, the unnamed writer goes on to note that "las opiniones se dividen; los historiadores se contradicen, discuten, disputan ardorosa, vocingleramente. Es que --como cumpliéndose otra de las predicciones de El Supremo-- esta iniciativa de unión natural se convierte en terreno donde apunta el brote de una diminuta guerra civil, afortunadamente incruenta, puesto que se trata sólo de un enfrentamiento 'papelario'" ["opinion is divided; the historians contradict each other, engage in heated exchanges, argue vociferously. As if in fulfillment of El Supremo's predictions, this epic national undertaking turns into a small-scale civil war, fortunately a bloodless one, since the confrontation takes place 'only on paper'" (Ibid.). Since Milagros Ezquerro reassures us that "los textos citados en el Apéndice son auténticos y no han sido modificados. Se notará que muchos de los hechos aquí evocados han sido aludidos han sido en el discurso de El Supremo" ["the texts cited in the Appendix are authentic and have not been altered. It will be noted that many of the events evoked here have been alluded to in El Supremo's discourse"] (597), I'll take the liberty of mentioning a lone nugget from Julio César Chaves' comment on the mood in Paraguay the year after the controversial Karaí-Guasú's death: "Es conveniente recordar que poco tiempo después apareció una mañana en la puerta del templo un cartel que se decía enviado por él, desde el infierno, suplicando se lo removiese de aquel lugar santo para alivio de sus pecados" ["We may here remind the reader that a short time later a placard appeared on the door of the church, stating that it had been sent by him from hell and begging that he be removed from that sacred place in order to lessen his burden of sin"] (601 in the original, 428 in the translation).

Whatever censure or praise the real life José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia deserves for the perpetual dictatorship role he played on the stage of 19th century Paraguayan history--he has been hailed as both the Robespierre of America and a terrible despot made crueler by mental illness--his polemical fictionalization by Roa Bastos is so artistically successful and entertaining that the recent real life historians' debate about the father of the Paraguayan revolution seems like just another chapter in our exiled novelist's master plan to novelize his country of birth. It is to be lamented that Roa Bastos' planned follow-up to Yo el Supremo, a "contrapunto picaresco" ["picaresque counterpoint"] to this work in the words of Milagros Ezquerro with the title Mi reino, el terror [Terror: My Kingdom], was eventually abandoned (16). On the other hand, Yo el Supremo is so thoroughly satisfying in its exploration of the intersections between history and literature that it feels a little wrong to complain about never being able to hold that unwritten book with the tantalizing title in my hands. On that note, I guess it's finally time to mention the ultimate ending of Yo el Supremo, a "Nota final del Compilador" [Final Compiler's note] in which we are told that "esta compilación ha sido entresacada" ["this compilation has been culled"] from a staggering number of other written sources, oral interviews and etc. (608 in the original, 435 in the translation). In a twist, we then read that "ya habrá advertido el lector que, al revés de los textos usuales, éste ha sido leído primero y escrito después. En lugar de decir y escribir cosa nueva, no ha hecho más que copiar fielmente lo ya dicho y compuesto por otros" ["the reader will already have noted that, unlike ordinary texts, this one was read first and written later. Instead of saying and writing something new, it merely faithfully copies what has already been said and composed by others"] (Ibid.). In other words, once again we are confronted with the notion of a collective as opposed to an individual authorship although expounded in such an ironic way that it undermines the authority of its own words. And in the final paragraph of the final ending to Yo el Supremo, the compiler gets one last chance to aggressively blur the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction and manages to make the most of it with an unexpected but perfectly fitting reference to another expanding universe of a novel, Robert Musil's The Man Without Qualities. I hope you enjoy it because this is the last I'll have to say about Yo el Supremo for a while (609 in the original, 435 in the translation):

Así, imitando una vez más al Dictador (los dictadores cumplen precisamente esta función: reemplazar a los escritores, historiadores, artistas, pensadores, etc.), el a-copiador declara, con palabras de un autor contemporáneo, que la historia encerrada en estos Apuntes se reduce al hecho de que la historia que en ella debió ser narrada no ha sido narrada. En consecuencia, los personajes y hechos que figuran en ellos, han ganado, por fatalidad del lenguaje escrito, el derecho a una existencia ficticia y autónoma al servicio del no menos ficticio y autónomo lector.

Hence, imitating the Dictator once again (dictators fulfill precisely this function: replacing writers, historians, artists, thinkers, etc.), the re-scriptor declares, in the words of a contemporary author, that the history contained in these Notes

is reduced to the fact that the story that should have been told in them has not been told. As a consequence, the characters and facts that figure in them have earned, through the fatality of the written language, the right to a fictitious and anonymous existence in the service of the no less fictitious and autonomous reader.

Bravo, senhor/señor Roa, bravo.

*In hindsight, a fairly clear anticipation of these endings and another approach to the dictator's legacy can be found in the extended passages where the Supreme's dog Sultán/Sultan abuses his former master: "¡Bah, Supremo! ¡No sabes aún qué alegría, qué alivio sentirás bajo tierra! La alucinación en que yaces te hace tragar los últimos sorbos de ese amargo elixir que llamas vida, mientras vas cavando tu propia fosa en el cementerio de la letra escrita" ["Bah, Supreme! You don't know yet what happiness, what relief you'll feel below earth! The delusion in whose toils you lie is making you swallow the dregs of that bitter elixir you call life, as you finish digging your own grave in the cemetery of the written word"] (542 in the original, 376 in the translation).

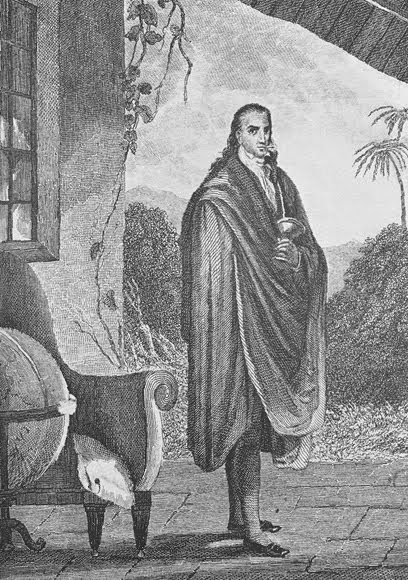

José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia strikes a dictatorial pose.

Thanks very much to Séamus of Vapour Trails for reading Augusto Roa Bastos' fantastic novel with me. Séamus' rousing post on I the Supreme/Yo el Supremo can be found here.

.jpg)