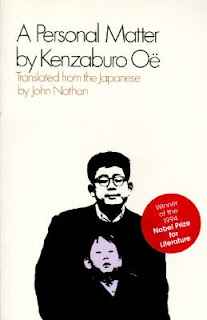

El testigo (Anagrama, 2007)

por Juan Villoro

México, 2004

"No me veas así, pendejo, este país sólo tiene una división geográfica importante: los cárteles".

(El testigo, 221)

Aunque leí el Premio Herralde 2004

El testigo como mi primer libro para el

Reto México 2010 de

Sylvia, había querido leerlo desde que vi que fue considerado como el número 18 en la lista de

Las mejores 100 novelas de la lengua española de los últimos 25 años según Semana.com (por supuesto, también tenía ganas de hacerlo porque sabía que Bolaño era hincha de Villoro). Sin ir más lejos, yo diría que para mí era un libro muy bueno pero quizá no era un excelente libro. Mientras que mi única queja de verdad es que Villoro a veces trataba de hacer demasiado con su argumento, la novela es una mezcolanza rica que se compone de una suerte de libro de viaje, una historia sentimental, y una trama novela narco entre otros ingredientes. El protagonista, Julio Valdivieso, es un profesor potosino que regresa a México después de unos veinte años que ha pasado enseñando en el extranjero. Al descubrir un nuevo país (al hablar de la política) y el mismo México de siempre (al hablar de las conexiones sentimentales con varios amigos y familares de su pasado), Julio gradualmente está metido en una crisis donde los recuerdos de un amor perdido, su afán por el poeta mexicano Ramón López Velarde, una telenovela que se prepara sobre la guerra cristera, y una serie de asesinos probablemente relacionadas con los narcotraficantes al margen de su círculo de socios todos tienen algo que decir sobre su futuro. Porque sospecho que mi resumen en miniatura de la novela les va a impresionar muy poco, me gustaría aclarar que me gustó el sentido de humor de Villoro (una proeza dada que la novela es basicamente un estudio psicológico). Julio vocifera injurias contra Supertramp en un párrafo entero al principio de la novela, por ejemplo, y ese grupo nefasto de

castratti con timbre nasal sigue ser la cabeza de turco del personaje a través de las 470 páginas siempre que haya mala suerte. ¡Muchas risas! Al mismo tiempo, Villoro me impresionó con su alcance como un maestro de ambiente, atmósfera y diálogo. Por eso quiero decir que ambos los contrastes entre las escenas urbanas en la D.F. y las escenas de campo en Los Cominos y el diálogo entre personas de estratos sociales distintos me parecieron fidedignos. Adémas, el capítulo donde Julio recibe una paliza de un policía corrupto me recordó de Bolaño con respecto a su intensidad. Aunque pienso que Villoro faltaba un poquitín de sutileza en lo que se refiere al estatus de Julio como un testigo a todos los cambios en México durante los últimos 25 años, ya puedo entender cómo algunos podrían opinar que ésta sea la gran novela mexicana de esta década. De hecho, me gustaría leer más de Villoro dentro de poco.

*

El testigo (Anagrama, 2007)

by Juan Villoro

Mexico, 2004

"Don't look at me like that, pendejo, this country only has one important geographical division: the drug cartels."

(El testigo, 221, my translation)

Although I read the 2004 Premio Herralde winner

El testigo [

The Witness, sadly not yet translated into English] as my first book for

Sylvia's

Mexico 2010 Reading Challenge, I'd wanted to read it ever since I saw it was ranked #18 on Semana.com's list of "The 100 Best Spanish-Language Novels of the Last 25 Years"

here (of course, it didn't hurt that I knew that Bolaño had been a fan of Villoro's as well). Without getting into all the details just yet, I'd say that this was a very good but perhaps not a great book in my estimation. While my main complaint is the somewhat nitpicky one that Villoro occasionally tried to cover too much ground with his plot, the novel's a rich hodgepodge of intersecting plotlines in which a sort of emotional-psychological travel journal, a love story, and elements of a narco-novel combine to form some of the main ingredients. The protagonist, Julio Valdivieso, is a professor from San Luis Potosí state in central Mexico who returns to the country after an absence of some twenty-odd years spent teaching abroad. Upon discovering a new country (politically-speaking) and the same old Mexico as always (in terms of his sentimental connections with various friends and family members from his past), Julio gradually becomes mixed up in a crisis where the memories of an old love affair that still haunts him, his fondness for the Mexican poet Ramón López Velarde, a soap opera in the making based on the Cristero War, and a series of killings probably involving narcotraffickers on the fringes of his social circle all will have something to say about his future. Since I suspect that this rapid fire summary of the novel probably wouldn't draw many new readers to it even if it were available in translation, I'd like to make it clear that I really, really enjoyed Villoro's sense of humor here (no mean feat in what's at heart a reflective, psychological study). Julio goes on a paragraph-long rant against the group Supertramp early on in the novel, for example, and that horrible band of nasally

castratti come up as targets again and again throughout the 470 pages whenever the character faces a new round of adversity. Just cracked me up. At the same time, Villoro also impressed me with his range as a master of mood, setting, and dialogue. Both the contrasts between the urban scenes in Mexico City and the country scenes at Los Cominos and the dialogue involving people from various social strata felt believable to me, and the part of the novel where Julio gets beat up by a dirty cop was Bolaño-like in intensity. So while Villoro might have laid it on just a little too thick for me in regards to Julio's status as a witness to the sweeping changes in Mexico over the last 25 years, there's enough cool stuff going on with his

El testigo that I can understand why some might view this as the Great Mexican Novel of the present decade. If everything works out, I intend to read more by the guy before too long.

Juan Villoro

Hay cosas que se detestan y otras que es posible aprender a odiar. Supertramp llegó a su vida como un caso más de rock basura, pero esa molestia menor encontró una refinada manera de superarse. El destino, ese croupier bipolar, convirtió las voces de esos castratti industriales en un imborrable símbolo de lo peor que había, no en el mundo, sino en Julio Valdivieso. Había educado su rencor en esa musica, sin alivio posible. Olía a caldo de poro y papa, el caldo que bebío en la cafetería de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, unidad Iztapalapa, el día en que Supertramp dejó de ser un simple grupo infame con sinusitis crónica para representar la fisura que él llevaba dentro, una versión moral de la sopa de poro y papa o del cáncer de hígado o alguna otra enfermedad que el destino tuviera reservada para vencerlo.

(El testigo, 19)

*

There are some things you hate and other things it's possible for you to learn to hate. Supertramp came into his life as just one more example of rock garbage, but that minor annoyance found a refined way to go beyond all that. Fate, that bipolar croupier, converted the voices of those industrial castratti into a symbol of the worst there was, not in the world but in Julio Valdivieso. He had forged his resentment in that music, with no relief possible. It reeked of potato and leek soup, the soup that he slurped at the Iztapalapa campus of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana the day in which Supertramp stopped being merely an odious group with chronic sinusitis and became a stand-in for the fissure he carried within himself, a moral version of the potato and leek soup or liver cancer or whatever other illness fate had in store to conquer him.

(El testigo, 19, my translation)

.jpg)

.jpg)