"Autobiografía de Irene," "La furia" & "Las invitadas" (Emecé Editores, 2009)

by Silvina Ocampo

Argentina, 1948, 1959 & 1961

En la puerta de un almacén tuve que presenciar la pelea de dos hombres. No quise ver el cuchillo secreto, no quise ver la sangre. La lucha parecía un abrazo desesperado. Se me antojó que la agonía de uno de ellos y el terror anhelante del otro eran la final reconcilación. Sin poder borrar un instante la imagen atroz, tuve que presenciar la nítida muerte, la sangre que a los pocos días se mezcló con la tierra de la calle.

[In the doorway of a store, I had to witness a fight between two men. I didn't want to see the hidden knife, I didn't want to see the blood. The struggle resembled a desperate embrace. I fancied that the agony of one of them and the longed for terror of the other was the final reconciliation. Without being able to erase that dreadful image for one instant, I had to witness the spotless death, the blood which in a few days would be mixed with the street's earth.]

(Autobiografía de Irene, 158, w/my translation)

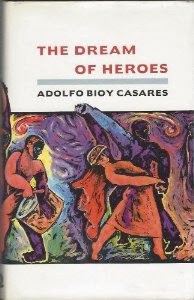

Given Silvina Ocampo's impeccable Buenos Aires cultural pedigree--she was, after all, the wife of Adolfo Bioy Casares, the close friend of Borges and J.R. Wilcock, and the youngest sister of

Sur founder Victoria Ocampo--should she really be considered as an Argentinean Literature of Doomster alongside all those full-on freaks like Osvaldo Lamborghini and Néstor Perlongher? That is, does she have the requisite street cred? Judging by the three title tales from her 1948, 1959 and 1961 short story collections, I'd say that the answers are probably, a resounding yes, and maybe, just maybe respectively. You, of course, are free to decide for yourself, hipster. "Autobiografía de Irene" ["Autobiography of Irene"] is prob. the most conventional of the three stories under consideration here, but it's really only conventional from a literature of the fantastic point of view: like a reverse Ireneo Funes from Borges' "Funes el memorioso," its weary 25-year old narrator Irene Andrade is afflicted with a strange condition in which she can see the future but can't remember the past (Irene/Ireneo, get it?). Knowing that her memories will only return as the anticipated hour of her death approaches, Irene takes advantage of the fateful day to reflect on how she predicted and mourned her father's death a full three months in advance, witnessed a knife fight that she knew would end fatally, watched kids pass by her balcony on the way to school bearing the faces of the adults they would eventually become, and even avoided trying to meet her future boyfriend because she foresaw how his life would end as a result of a date with destiny with an oncoming train. Wouldn't having clairvoyant powers have its compensations, though? Not in Irene's world where, paper rose in hand, redolent of loss, she says that she was happy before her father's death--"si es que existe la felicidad" ["if, that is, happiness exists"] (157). Feeling guilty for having caused or at least not having been able to do anything to prevent the death of her loved ones, she later adds how she fervently wished for "la muerte, única depositaria de mis recuerdos" ["death, sole repository of my memories"] (160). A circular narrative structure (the story ends with the same words with which it begins) and the arrival of an unknown woman (Irene's doppelganger?) may lead the reader to question whether the narrator has finally died or is just stuck in a metaphysical endless loop with or without a double in tow. Ocampo's gruesome but vividly written "La furia" (translatable as either "The Fury" or just "Fury" as the story plays off both the mythological and the non-mythological significance of the word in its tale of a young child's murder), on the other hand, is surely an undeniable Doom urtext in the sense that it's almost as disturbing as, say, Marcel Schwob's

"Blanche la sanglante" ["Bloody Blanche"] or Alejandra Pizarnik's

"La condesa sangriente" ["The Bloody Countess"] from a thematic point of view. Even if the confession of a madman style resolution of the story is less structurally inventive than the one provided by the earlier "Autobiografía de Irene," its wild writing and lurid, nightmarish imagery help make up for that deficiency. Winifred, the supposed love interest of the unnamed narrator, is introduced to us as the Filipina nanny of a young Buenos Aires child: "La conocí en Palermo. Sus ojos brillaban, ahora me doy cuenta, como los de las hienas. Me recordaba a una de las Furias" ["I met her in Palermo. Her eyes were shining, I now realize, like those of a hyena's. She reminded me of one of the Furies"] (230). During her Saturday afternoon trysts with the narrator, Winifred cops to how she accidentally killed her best friend Lavinia as a child in the Phillipines by setting her angel wings on fire when they were both dressed up for a feast day of the Virgin Mary celebration. Shades of the Lavinia from

The Aeneid, "ripe for marriage," whose hair catches on fire during a sacrifice at the altar? Perhaps. But suffice it to say that the little angelic friend met her end "carbonizada" ["carbonized"] (232), a revelation that eventually leads our schoolboy narrator to suspect that Winifred only "quería redimirse para Lavinia, cometiendo mayores crueldades con las demás personas. Redimirse a través de la maldad" ["wanted to redeem herself for Lavinia, committing greater cruelties against other people. Redeeming herself through evil" (234). Sounds heavy and yet, how I do explain the humor of the scene where Winifred wants to etch the narrator's name and hers boyfriend/girlfriend style on the most pornographic graffiti-ridden surface in a public park? Or the surrealistic strangeness of the scenes involving little plates of milk left outside Winifred's home to ward off vipers or her accounts of the dead rats and live spiders placed in loved ones' beds by the presumably kinder, gentler childhood Fury? Since "Autobiografía de Irene" and "La furia" both touch on the notion of childhood trauma in their own dramatically different ways--the earlier story with its pensive and world-weary tone and its suggestion that there's nothing that can be done to thwart fate, the latter with its figurative aesthetic representation of a cracked fairy tale-like kingdom where a minotaur stalks the perfectly manicured and otherwise opulent prose grounds--I suppose it's only fitting that "Las invitadas" ["The Guests"] offers yet another approach to the same general topic (Ocampo is both imaginative

and obsessive, you see). However, this particular offering showcases a much more humorous side of the writer via a story in which young female personifications of the seven deadly sins mysteriously show up at a young boy's birthday party to initiate him into the world of adulthood. While the laughs here are largely situational--as in the case of the batty old maid who, left alone to take care of the boy while his parents are on vacation in Brazil, wants to serve the young boy his birthday cake for breakfast because "por la tarde la torta cae pesada el estómago, como la naranja que por la mañana es de oro, por la tarde de plata y por la noche mata" ["just like oranges are gold in the mornings, silver in the afternoon, and kill you at night, cake is too heavy on the stomach in the afternoon"] (473)--the larger, lost in translation irony is that nobody but the birthday boy Lucio is expecting any guests because he's home sick with the measles. That is, all the

invitados (male and female guests) have said they would stay away from the party for fear of contagion; only Lucio foresees the arrival of

las invitadas (female-only guests) when they knock on the door and he smoothes down his hair in the mirror in preparation. "Ningún varón entre todos estos invitados" ["No male among all these guests"] exclaims the maid. "¡Qué extraño!" ["How strange!"]. The upshot of all this? According to the maid, Lucio ends up developing a crush on the scheming girl who "supo conquistarlo sin ser bonita. Las mujeres son peores que los varones" ["knew how to conquer him without being good-looking. Women are worse than men"] (476). And the punchline that immediately follows?

Cuando volvieron de su viaje los padres de Lucio, no supieron quiénes fueron las niñas que lo habían visitado para el día de su cumpleaños y pensaron que su hijo tenía relaciones clandestinas, lo que era, y probablemente seguiría siendo, cierto.

Pero Lucio ya era un hombrecito.

[When Lucio's parents returned from their trip, they didn't learn who the girls were who had visited him on his birthday and they thought that their son had clandestine relationships, which was, and probably continues being, true.

But Lucio was already a little man, un hombrecito.]

Note: according to the number of candles on his birthday cake, a six year old hombrecito at that!

Source

These three stories appear in Silvina Ocampo's

Cuentos completos I (Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1999) on pp. 153-165 ("Autobiografía de Irene"), 230-236 ("La furia") and 473-476 ("Las invitadas"). On a related note, Rise of

in lieu of a field guide reviewed Ocampo's "The Golden Hare" ["La liebre dorada"], one of the few stories from

La furia to be translated into English to date, as part of last year's ALoD. Check out his post

here.

.jpg)

.jpg)