por Gabriel García Márquez

Colombia, 1986

"También los que se quedaron son exiliados".

(La aventura de Miguel Littín clandestino en Chile, 47)

Qué agradable, qué absolutamente agradable, para poder despedirme del año de lecturas de 2010 con esta pequeña joya de un librito. El año es 1985. Luego de una larga ausencia en exilio en el extranjero, el cineasta chileno Miguel Littín, "que figura en una lista de cinco mil exiliados con prohibición absoluta de volver a su tierra", se resuelve a regresar a Chile para rodar un documental sobre "la realidad de su país después de doce años de dictadura militar" (7). Pretendiendo ser un hombre de negocios uruguayo con papeles falsos y un acento uruguayo poco convincente, Littín pasa seis semanas clandestinamente en Chile trabajando con tres equipos de cine europeos para poner "una larga cola de burro para Pinochet" (22). ¡Cómo me encantó esta obra! Aunque se lee como una novela de espionaje narrada en primera persona, los momentos culminantes de este reportaje de no ficción subrayan la opresión del régimen Pinochet y la voluntad del pueblo chileno para vivir con dignidad a pesar de las dificultades políticas. Punto: las llamadas "flores eternas" en la Plaza Sebastián Acevedo, donde Littín nos cuenta del "ramo de flores perpetuas mantenidas por manos anónimas" en honor de Sebastián Acevedo, un minero que "se había prendido fuego en ese sitio, dos años antes" como una protesta pública contra la tortura de su hijo e hija (86-88). Punto: la dueña de la casa donde "había una imagen de la Virgen del Carmen" (la patrona y "generala" del ejército chileno) que responde a la pregunta de si ella "había sido allendista" así: "No lo fui: lo soy". Y lo prueba por quitar la imagen de la Virgen para mostrar un retrato de Allende escondido detrás (104-105). Punto: los grafiti a la casa de Pablo Neruda en Isla Negra, donde además de los mensajes de amor esperados se encuentran otros mensajes menos esperados: "El amor nunca muere, generales; Allende y Neruda viven; un minuto de oscuridad no nos volverá ciegos" (111-112). Conmevedora por completo, esta obra es redimida por un final feliz para Littín y por lo que parecería ser un excelente trabajo de redacción por García Márquez, la figura del "autor" en las sombras. (Debolsillo)

Clandestine in Chile (NYRB Classics, 2010)

by Gabriel García Márquez [translated from the Spanish by Asa Zatz]

Colombia, 1986

"Those who stayed behind are also exiled."

(La aventura de Miguel Littín clandestino en Chile, 47 [my translation])

How cool, how absolutely cool, to be able to close out my 2010 reading year with this little gem of a book. The year is 1985. After a long absence in exile abroad, Chilean film director Miguel Littín, "who figures among a list of 5,000 exiles absolutely forbidden to return to their country," resolves to return to Chile in order to shoot a documentary about "the reality of his country after twelve years of military dictatorship" (7). Passing himself off as an Uruguayan businessman with false papers and an unconvincing Uruguayan accent, Littín spends six weeks undercover in Chile working with three European film crews to try and "pin the tale on the Pinochet donkey" (22). My, how I loved this work! Although it reads like a spy novel, the key moments in this first-person, non-fiction account poignantly underscore the Pinochet regime's oppressive nature and the will of the Chilean people to live with dignity in spite of the political difficulties. Item: the so-called "eternal flowers" in the Plaza Sebastián Acevedo, where Littín tells us about the "bouquet of flowers perpetually maintained by anonymous hands" in honor of Sebastián Acevedo, a miner who "had set himself on fire on that site two years earlier" in public protest against the torture of his son and daughter (86-88). Item: the homeowner with a statue of the Virgen del Carmen (the patron saint and "female general" of the Chilean army) who, when asked if she had been a Salvador Allende supporter, replied emphatically: "Not I was; I am." And then proved it by moving aside the Virgin's image to reveal a portrait of Allende hidden behind it (104-105). Item: the graffiti at Pablo Neruda's house in Isla Negra, where alongside the expected messages having to do with proclamations of love could also be found messages of a less expected nature: "Love never dies, Generals; Allende y Neruda live; one minute of darkness won't turn us blind" (111-112). Devastating stuff all in all and yet redeemed by a happy ending for Littín and what appears to be an exquisite editing job by García Márquez, the reclusive "author" of the filmmaker's story [note: all translations mine with page numbers based on the Spanish version of the work]. (http://www.nyrb.com/)

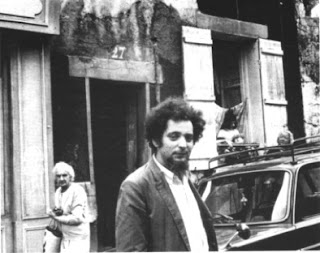

Gabo, Geraldine Chaplin y Miguel Littín, hacia 1980

.jpg)