"The insidious power of this book convinced me that I need to collect all of Aira in English."

Rise, in lieu of a field guide, details below*

The Argentinean Literature of Doom: Año 2 bacchanalia is now over, kind of, but there's no need for any of you to get depressed about it just because Osvaldo Lamborghini was a no-show this year. Of course, weeping and gnashing of teeth are still acceptable and even encouraged forms of behavior under the circumstances. In any event, here's December's Doom link action (November's links can be found here) with a special thanks to Scott for supplying another great César Aira post and an appreciative thanks to Rise, Scott, and Tom for playing along in the first place. You guys are hardcore!

Richard, Caravana de recuerdos

"Torito" by Julio Cortázar

El camino de Ida by Ricardo Piglia

"El uruguayo" by Copi

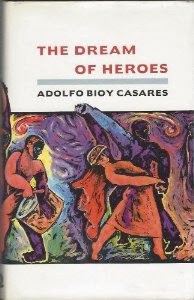

El sueño de los héroes by Adolfo Bioy Casares

Autobiografía de Irene by Silvina Ocampo (edit: link added 1/14)

Las armas secretas by Julio Cortázar

Los Fantasmas by César Aira

La última de César Aira by Ariel Idez

Scott, seraillon

Since I've fallen behind on my ALoD:A2 reviews and, let's face it, am probably far more likely to flake out than to deliver a reasonably coherent post well after the fact anyway, I thought I'd assemble an all-tournament team for the event for your imaginary reading pleasure. In no particular order, such a team would have to consist of César Aira's The Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira (still unread by me but raved about by all the other "judges" on the "panel") and Los Fantasmas, Adolfo Bioy Casares' El sueño de los héroes, and Juan José Saer's El limonero real among the novels and novellas and Copi's "El uruguayo," Julio Cortázar's "Torito," Silvina Ocampo's "El impostor," and Néstor Perlongher's "Evita vive" among the short stories (*Rise, so often ahead of his time in these matters, wrote a great short reaction to the translation of Los Fantasmas [Ghosts] way back in 2010--please check it out). A stellar bunch all in all: longtime favorites Fogwill and Ricardo Piglia got left off the team even though I loved the stuff I read by them, and I could have easily added more/different Cortázar and Ocampo stories. Go figure.

.jpg)